What Nobody Told Me About AI Evaluation

The systematic evaluation process that separates demos from production-quality applications.

AUTHOR

Nathan Horvath

PUBLISHED

2025-08-17

Last year, I worked with a team on a chatbot for an innovation competition. The system used retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) to search through company dashboard metadata and recommend relevant dashboards to users. Building the initial version was straightforward. Making it work reliably for even our tiny demo felt impossible.

Our evaluation process consisted of five test queries with the LLM's temperature set to zero for consistent outputs. Getting acceptable answers for just those five queries turned into whack-a-mole. Try to fix query #1, break query #3. Add context for query #4, confuse query #2. We eventually got something demo-worthy by essentially overfitting to those specific questions. There's no way this process would have scaled effectively beyond these five queries.

I didn't know any better at the time. Neither did my team. We assumed this random tweaking was just how AI development worked.

Now I see this "prompt and pray" pattern repeatedly. Teams demo a promising proof-of-concept with no transparent or systematic process for improvement. Maybe they're doing something behind the scenes, if their tools even allow changes beyond prompt tweaking, but the approach often seems just as haphazard as ours was.

Before taking AI Evals For Engineers & PMs with Hamel Husain and Shreya Shankar, I thought newer models or better prompts would eventually solve these problems. I had no framework for understanding why some AI applications stayed mediocre while others improved.

The course highlighted what I'd been missing. We were stuck because we were skipping 80% of the actual work. Most of the effort in building production AI goes into evaluation, error analysis, and systematic improvement, not feature development. As a data scientist, I realized I already had these fundamental evaluation skills. AI applications need the same rigour, just with some variations of familiar tools. We just need to apply these principles we already know.

Looking back at our chatbot, I see exactly what went wrong and what we should have done instead. More importantly, I understand why this problem is universal. Everyone's racing to build AI products with cutting-edge features. Meanwhile, the winners are building sustainable evaluation systems.

The Evaluation Reality Nobody Wants to Hear

The course revealed an uncomfortable truth that most teams don't want to hear: building production AI applications means spending 80% of your time on evaluation work, not feature development. This isn't just a temporary phase, but the permanent reality of maintaining quality AI systems.

This ratio feels wrong because our instincts push us toward building. We want to add new capabilities, experiment with different models, and implement sophisticated architectures. Reviewing hundreds of traces, categorizing failures, and building evaluation frameworks sounds like grunt work. I've heard colleagues dismiss this manual work entirely, suggesting it should be outsourced to an LLM or automated tool, as if the analysis itself is the problem rather than the solution.

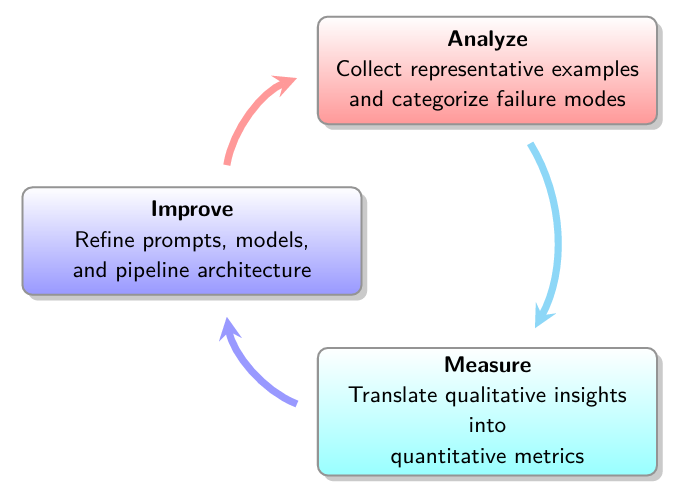

There's a systematic process that transforms this seemingly mundane work into predictable improvement: the Analyze-Measure-Improve cycle.

Analyze–Measure–Improve cycle from the AI Evals for Engineers & PMs course

This cycle addresses the fundamental challenges of working with LLMs. During Analyze, you're essentially debugging why your AI doesn't understand what you want. By manually reviewing traces, you uncover whether failures stem from unclear instructions, inconsistent behavior across inputs, or something else entirely. Some issues become immediately obvious, like ambiguous prompts that need rewriting. Others reveal themselves as patterns that need investigation before you can properly address them.

That's where Measure comes in. You can't fix what you can't quantify. For those complex failure patterns discovered during analysis, you build evaluators (evals for short) to get hard numbers quantifying how often specific failures occur, especially those needing further root-cause analysis. This data is crucial in transforming gut feelings into a strategic action plan.

The Improve phase is where you actually fix things, but now you're working with precision instead of guesswork. Quick wins like clarifying prompts can happen immediately. Deeper issues might require adjusting your retrieval strategy, engineering better examples, or even changing your architecture. The key is that every change is targeted at a specific, measured problem.

Together, these steps create a powerful feedback loop. Each iteration sharpens your understanding of what the AI struggles with and why. This lifecycle ensures you're building institutional knowledge about how your specific AI application behaves in the real world.

Looking back at our chatbot, here's what we should have done if we'd wanted to move from proof-of-concept to production quality. We would have gathered dozens of potential user queries, reviewing full traces to understand where and why the system failed. We might have discovered patterns like the system conflating dashboard names when users used abbreviations, or consistently missing relevant dashboards when queries mentioned specific metrics.

Through this error analysis, we'd develop a rubric with specific criteria tied to these failure modes. Instead of vague goals like "helpful responses", we'd define concrete pass/fail criteria, such as: "correctly identifies the requested dashboard", "retrieves all dashboards containing the specified metric", "includes dashboard URLs in responses".

Some of these criteria could be evaluated with simple code checks. Does the response include a valid URL? Are valid dashboard names mentioned? Others would require LLM-as-judges primed with our specific rubric to catch nuanced failures, like incorrect dashboard purpose descriptions or missing context about dashboard capabilities.

The Improve phase would target our highest-impact failures first. If 60% of failures came from abbreviation confusion, we'd focus there before addressing edge cases. After implementing changes, we'd run our evaluation suite to verify if any change made to the AI system actually resulted in improvement to our performance metrics, rather than just hoping an improvement happened.

This process transforms random experimentation into systematic engineering. You know exactly which failures to address, how to measure improvement, and whether changes actually help.

The Cost Nobody Wants to Pay

During course office hours, one question surfaced repeatedly: "How do you sell the evals process?" The answer is simpler than people expect: do some basic error analysis and show stakeholders what their AI actually does. Gather real inputs and outputs, categorize the failures, and present the reality. Then ask if they're satisfied with that quality. If they are, fine. But make it clear the system won't improve without systematic evaluation.

When stakeholders see this reality and hesitate, their response reveals their misconceptions about what AI actually is. Many people, especially those without technical backgrounds, were sold the idea that AI is an oracle that can do anything without needing priming, just like magic. When they unbox the product and it doesn't meet expectations, they turn to their engineers. But the engineer can't fix it alone, as they lack the domain expertise needed to identify what "good" actually looks like. No AI system has this definition of good preloaded out-of-the-box.

This disconnect creates the resistance. Domain experts understand what "good" looks like for specific business processes, yet they're rarely given adequate time to review AI outputs. Managers either can't afford to pull them from existing work, or when they do allocate them, it's added on top of their regular workload without reducing other responsibilities. This setup guarantees rushed, surface-level reviews rather than the deep analysis needed.

Beyond the human cost, there's the technical evaluation burden that multiplies with every architectural decision.

Start with the simplest evaluators possible. Code-based checks handle many failure modes effectively. If your system needs to include a URL, a regex works. If responses must stay under a word limit, basic counting suffices. These evaluators are fast, deterministic, and free to run.

Many failures require nuanced judgment that code can't capture. Evaluating tone, summary quality, or policy adherence requires LLM-as-judges primed with your specific rubric. Each judge needs carefully curated examples and validation against human judgments. A complex application might need five different judges if those failure modes can't be caught with simpler checks.

Architectural complexity compounds this burden. Adding RAG means evaluating both retrieval quality (are the right documents fetched?) and synthesis quality (are they used correctly in the response?). You should start with the simplest RAG implementation that addresses your identified failure modes, not the sophisticated vector database vendors are pushing. Similarly, agents multiply challenges exponentially. Every tool call, decision branch, and state transition becomes a potential failure point needing evaluation.

Even good applications degrade without ongoing evaluation. User behavior evolves, external factors shift, and what worked yesterday becomes inadequate today. Without evaluation infrastructure, silent failures accumulate as your system drifts.

The clear takeaway is to start simple and only add complexity when evaluation proves you need it. Every piece of complexity has an evaluation tax. Make sure the benefits justify the cost. But first, make sure everyone understands that AI isn't magical and actually requires systematic evaluation and continuous expert involvement.

The Questions Nobody's Asking

The difference between successful AI applications and perpetual prototypes comes down to whether teams are engineering solutions or gambling on improvements.

Here are the questions you can ask that reveal whether an AI project has a real path forward:

- Have you manually reviewed your traces to understand where and why your system fails?

- Which team members review outputs, and how often?

- What specific criteria define success or failure for your application?

- How do you measure whether changes actually improve your system?

- What's your process for continuous improvement after deployment?

- How will you detect when your system eventually starts degrading?

Without solid answers, teams are stuck in "prompt and pray" mode, making changes without measuring impact.

Since taking the course, I'm much more attuned to what's needed for AI success. I actively look for whether individuals or teams have thought about evals, whether domain experts are involved, and whether there's a real methodology behind "we'll iterate". The absence of these elements signals that an application will likely stagnate at whatever quality the initial prototype achieved.

This knowledge has shaped how I think about my career trajectory and where I see the field of data science heading. Chris Albon recently described an "AI Scientist" as someone better at data science than any AI engineer and better at AI engineering than any data scientist. This role fills a current gap by bridging domain expertise and AI implementation, bringing evaluation rigour from data science to AI development. Data scientists are uniquely positioned for this evolution because we understand evaluation methodology and statistical thinking.

Any data scientist, engineer, or product manager building AI applications needs this evaluation foundation. Without it, you're flying blind, unable to distinguish between genuine improvements and lucky guesses.

What I appreciated most about the course was discovering I wasn't alone in these struggles. The office hours discussions revealed practitioners across industries facing the same resistance, asking the same questions, trying to convince their organizations that evaluation isn't optional overhead but the actual work. Learning from instructors who've implemented dozens of AI systems gave me confidence that there's a proven path forward.

I came to the course trying to understand why our chatbot improvements felt directionless. I left understanding why most AI never gets better and what it actually takes to build AI that does. The systematic evaluation process exists and is learnable. For those tired of watching AI projects plateau after promising demos, start asking the uncomfortable questions about evaluation. Demand concrete answers about how teams measure improvement.

The choice is clear: if you want to move beyond proof-of-concept quality, invest in systematic evaluation. Otherwise, keep gambling that random changes will somehow make things better.